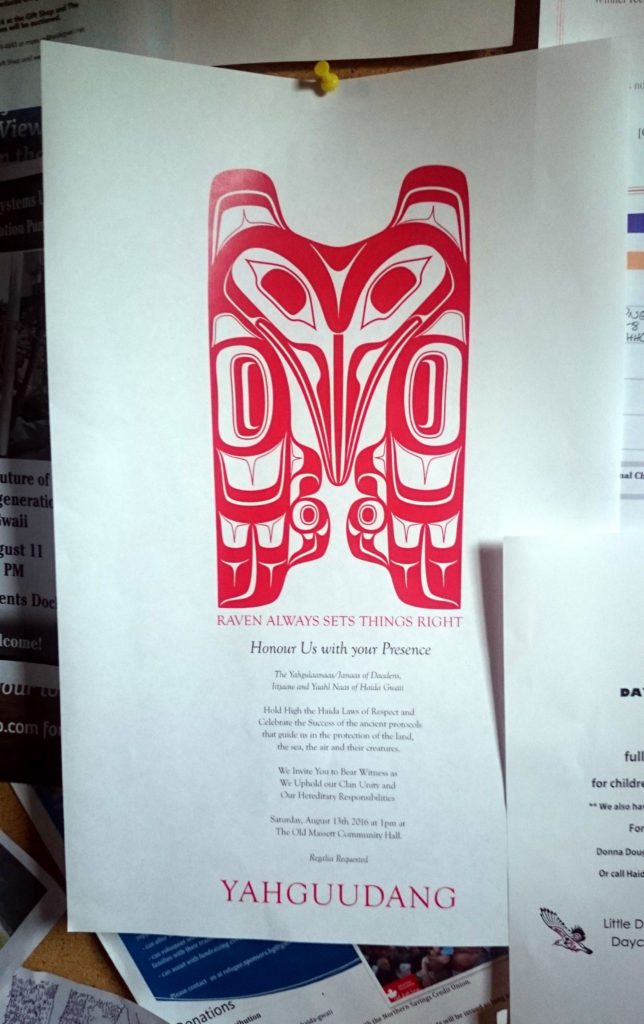

Raven Always Sets Things Right

by Karl Frost

On August 13 of this year, I had the honor to witness and document an historic potlach on Haida Gwaii held by the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas clan, “Raven Always Sets Things Right”. In the feast, the clan disrobed (removed from their positions of leadership) two house chiefs who were found to have betrayed and lied to their clan in secretly supporting the destructive and heavily opposed Enbridge tar sands oil pipeline. In supporting the pipeline, they represented themselves in their roles as hereditary chiefs, thus bringing shame on the clan. After much processing and community meeting, the clan decided to disrobe the two using traditional practices that had not been used in living memory. In doing so, the clan set an example for other Haida clans and other First Nations in how to deal with the ‘divide and conquer’ tactics of industry trying to make quick profits at the long term expense of the environment and community’s ability to support themselves. The feast was quickly picked up by media and has caused a major stir amongst First Nations communities and activists working to defend the environment.

Although the clan and others went into the feast nervous about such a serious action, the event itself was a joyous and well-supported celebration of doing things in a good way and standing together against short-sighted and greedy industrial interference. Dancers, singers, and drummers set the tone of the event, with carved Haida masks of raven, eagle, and many others. The business was carried out respectfully and clearly, as was witnessed and celebrated by visiting chiefs from around Haida Gwaii and the region who attested to its importance. Likewise, all of those assembled filled the halls with cheers and danced together to embody their felt experience of unity. The feast was a physical demonstration of the unity of the Haida.

Background: Oil, gas, and other issues

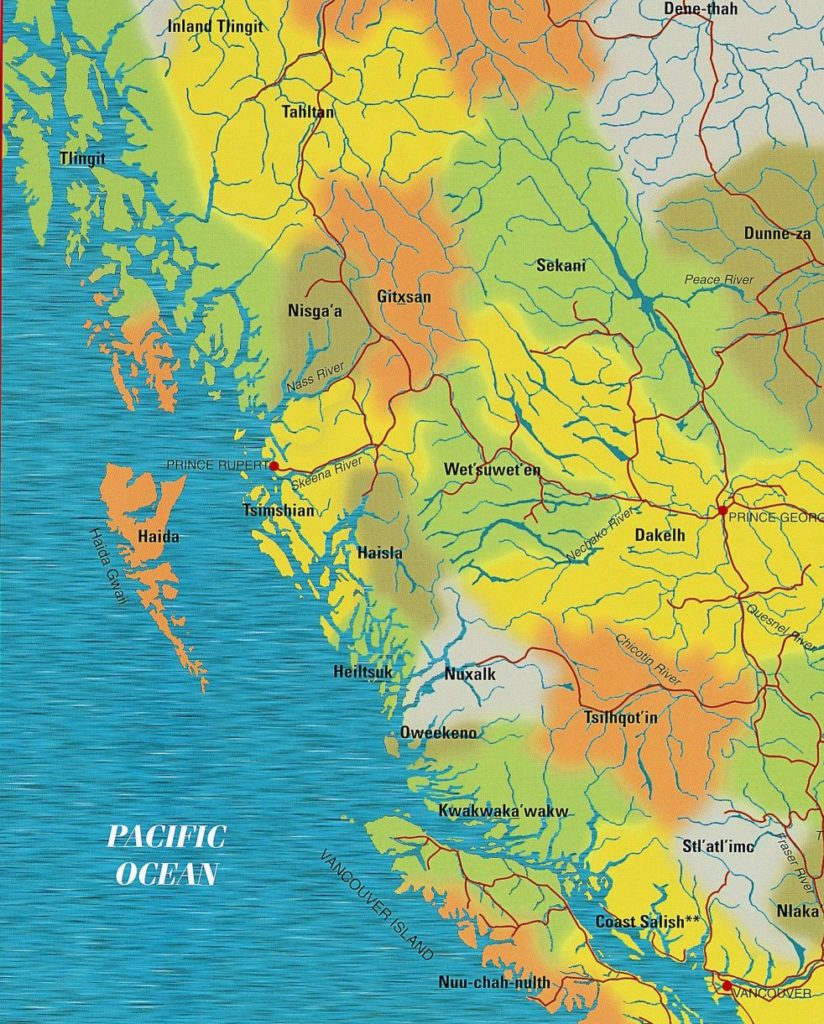

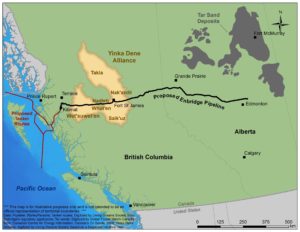

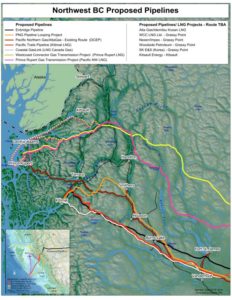

For the last several years, Enbridge has been trying to force through the Northern Gateway Pipeline to carry toxic tar sands oil (bitumen) from the Alberta oil patch to the north coast of British Columbia. Having bitumen supertankers moving through these waters is such a clear threat to the salmon and livelihoods of peoples in the region that many of the First Nations have declared that any act to construct such a pipeline would be seen as an act of war against their nations by Canada. The resistance to the pipeline has been outspoken and vibrant in communities, indigenous and non.

The threats to peoples throughout BC from any of these oil or gas pipelines is very real. As is often repeated, it is not about ‘if’ but ‘when’ an accident will occur if these tankers are allowed to move through the dangerous and hard to navigate waters of northern BC. There is a litany of risks throughout the process, from source through pipelines through tanker transport through end-use fuel consumption, but for the Haida a focus on tankers comes because of the inevitability of an accident in their waters and the inability to deal with it. As Haida carver and legal scholar Bernard Kerrigan explains, tankers are currently allowed off the west coast of Haida Gwaii, but there is a large buffer zone they are not allowed to move through. Last year, a tanker lost power and started drifting toward Haida Gwaii. It took 16 hours to mobilize the emergency response and get the tanker back under control. Tankers carrying tar sands oil from Kitimat would move within an hour of the Haida coast. A similar incident would spell unmitigated disaster for Haida Gwaii and the northern coast. Such a disaster is on top of a litany of other impacts, including the regular dumping of oil and ballast into coastal waters that these tankers would do as part of their regular operation. Speaking of the impacts of the movement of oil on the coast, Lisa White of the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas clan said, “We eat everything here… sea urchins, chitons, muscles, octopus, fish, crabs. It’s not worth any amount of money, that risk.” As Darin Swanson (Yahgulaanaas chief who put on and presided over the feast) said, they stand firm against all of these oil and gas projects, both for the impacts on their own waters and out of a sense of solidarity with other nations that could be affected in different parts of the pipeline and production chain.

Governance

The Haida are a matrilineal society, with clan identity coming from one’s mother. There are about 30 Haida clans divided into two ‘moeities’, Raven and Eagle. The Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas are of the Raven moiety. Clans are exogamous, meaning that one is expected to marry outside of one’s clan and moiety. Each clan is then divided into a number of houses (3 in the case of Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas), each with its own chief/spokesperson. As a new chief is identified, the role will usually go to the eldest son of the current chief’s eldest sister, unless it is decided somehow that this person would not be a good fit. The son of a chief will, of course, belong to a different clan, so it would not be appropriate for them to take on the role. This is one amongst many mechanisms that maintains women’s power amongst the Haida.

The one identified as next in line for chief is then nurtured from a young age into the role and is expected to shadow the current chief in clan business for many years before they assume the role themselves. The Haida name for the role referred to in English as ‘chief’ is ‘litl’xaaydaGa’. It doesn’t exactly mean what we might think of with the English word ‘chief’. Specifically, it is not a position of hereditary right to dominance or decision-making in a hierarchy. Instead, as Darin Swanson (litl’xaaydaGa Ginaawaan) explains, the role is better understood as spokesperson for a big family. It is a position of responsibility which obliges one to consult with and listen to the clan, particularly the matriarchs, and to act on their expressed desires.

As Kerrigan explains, “In Western Culture, people think of a chief as a king that dictates everything. In truth, a chief is a spokesperson for the clan, looks after the clan, and does whatever they can to make sure the clan is healthy and does well. The Chief should be the hardest working person, doing the most to protect the land, protect the people, make sure the people have food. Going along with an oil company who would destroy the environment would be a problem [inconsistent with the role of chief].” The role of litl’xaaydaGa is less about rights and more about duty… duty to listen to matriarchs and clan, and responsibility to transparent communication and dealings that reflect the will of the matriarchs.

The colonial process of overt and deliberate cultural suppression by the white Canadian government damaged the institutions of feasting and traditional governance. The previous Ginaawaan had to hold his potlach in secrecy in his home for fear of being arrested by the oppressive and abusive Canadian state. With so much of the population being stolen from their homes and forced into residential schools and foster homes, many grew up without the traditional guidance of elders in traditional ways and values. Despite all this, traditions and values were preserved and traditional culture has been seeing a steady resurgence. We are also entering a new era, where supreme court rulings have backed the political legitimacy and power of traditional governance through the hereditary chiefs, as opposed to the imposed Indian Act Band Councils[1]. In this context, clans are finding new power through traditional governance and, at the same time, industry is using new tactics to undermine these means to power.

Divide and Conquer: Lying to the clan and matriarchs

The Haida have established unity as a people in standing firm against the movement of oil through their waters. However, in early spring, there were rumors circulating within Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas that two of their litl’xaaydaGa, Carmen Goertzen and Francis Ingram, had been working on the sly in support of Enbridge and that they had been paid by Enbridge to do so. Goertzen and Ingram were called to a clan meeting and denied the rumors, committing to their responsibilities of transparency and following the lead of the clan matriarchs.

However, in June a letter to the National Energy Board supporting Enbridge’s permit review process was made public, signed by the two, along with 6 other Haida of other clans (including two other litl’xaaydaGa). The 8 had together formed a corporation called “The Hereditary Chiefs of North Haida Gwaii LLP”, under the name of which they signed the letter. The letter urged the National Energy Board to approve Enbridge’s request for an extension on their review process[2]. Simultaneously an unsigned term sheet was made public in which Enbridge promised $90,000 to each signer of such a letter and an additional $10,000 for the forming of such an LLP. The term sheet also required them to not say anything about the contract. As the chiefs at the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas potlach reiterated multiple times, these chiefs did not have a right to do this while holding the role of litl’xaaydaGa, being obliged in political engagements to support the will of the clan and matriarchs. In so doing, they violated their commitments to their clan and matriarchs and lied to them publicly.

This is a growing strategy of the oil and gas corporations, the setting up of what many are starting to call ‘rent-a-chief’ companies to give an illusion of legitimacy to the companies’ projects and to confuse the public through deceptive media announcements. They will say that they have First Nations leadership signing on to various environmentally and socially destructive agreements, when the real leadership is actually highly opposed. As another example, a similar organization was set up calling itself ‘the Nine Tribes of Lax Kw’alaams’, composed of non-chiefs and a few contentiously representing themselves as chiefs, in order to sign agreements with the Eagle Spirit oil company and as a vehicle for attacking the Tsimshian leadership occupying and defending Lelu Island against the Petronas LNG project (endangering the salmon of Skeena River). Another example is the Office of the Gitksan Hereditary Chiefs, representing themselves as an organization of all the Gitksan chiefs and getting paid by and signing on with pipeline companies with less than 7% of the Gitksan hereditary chiefs represented by the organization.

Once the NEB letter was discovered, a counter letter was sent from the Haida leadership to the NEB, reaffirming the Haida’s adamant opposition to oil and gas projects in the region and saying that these two chiefs do not speak for the collective of the Haida hereditary chiefs, as they represented themselves via their LLP. The two were also called in to clan meetings to explain themselves and so the clan could help them set things right for themselves. When confronted over lying to their own clan, there responses were reported to be aggressive and defensive. They declined to take part in any subsequent meetings of the clan over the issue. As reported by Swanson and others, their only response after initial aggressive and defensive denials was “I can’t talk”, one of the requirements of the term sheet for the money they were offered. While Goertzen initially claimed to have not received money from Enbridge or to have agreed to any payments from them for his choice, this was contradicted by Ingram (who was questioned separately). Dayaang (Donald Bell), one of the other Haida chiefs who attended and spoke at the feast, spoke to loud cheers of receiving one of these $90k offers himself and of throwing the letter out. As he and others pointed out, the Haida are a proud people and hold strong work ethics and principled commitment to defending the ability of their grandchildren and their grandchildren’s grandchildren to be able to live off the land and seas as they have done since time immemorial.

Goertzen and Ingram failed to take any of the opportunities offered by the clan to make amends for this breach of trust and violation of their duties as litl’xaaydaGa, and in fact failed to communicate at all with the rest of the clan after the initial confrontation with the letter. The clan decided to use traditional practices and hold an ‘emergency’ potlach, organized on 5 weeks’ notice to disrobe them. Such a feast has not been held since before the time when the Haida population was devastated by the ravages of disease and colonialism[3]. This action was not taken lightly and was the result of extensive community process. The two were invited by the clan up until the day of the feast itself to set things right themselves by rescinding the letter to the NEB and signing a letter as chiefs that they were against tankers moving through their waters.

The two had their positions and chiefly names taken from them as much for their betrayal of the clan in supporting Enbridge as for their lack of honesty in dealing with the clan, lack of willingness to listen to and take direction from the matriarchs and clan, especially when representing themselves as hereditary chiefs. As Kerrigan explained, it was done as non-aggressively as possible, but the clan had to remove the chiefs and replace them with people who would follow their culture, would look after their communities, resources, and environment and who would listen to the clan. This was difficult emotionally for the community. This distress in the end was also a repeated reason for their removal as chiefs. As Swanson spoke during his speech at the feast, expressing the sentiments of the clan, “This a blatant disrespect to our matriarchs, forcing them to make these emotionally difficult decisions.” It was emphasized repeatedly that it should never be the case that a member of the clan, especially litl’xaaydaGa, should cause such distress to their elders.

The two treated their positions more as ‘right holders’ than as ‘duty holders’. In disrobing these chiefs, the clan set things right. It was done respectfully and was a manifestation of a powerfully felt sense of unity.

As Kerrigan said, these divide and conquer tactics are frequently used by industry, paying off a few people to agree with the company and sign off on some papers. The company can then go to the courts and say ‘we have them agreeing with us’. It is then the onus of the people to prove in the courts that those signatures are not legitimate or representative of the nation. Thus, one gets ‘as much justice as one can afford’ in the courts. When the nations have budgets of thousands, court cases cost millions, and the companies can potentially make billions, the nations get bled of resources. This is also not just one industry, but instead dozens of companies with dozens of projects, depleting the community of its resources as it attempts to defend itself in the court system.

Potlaches are huge events, which require those holding the event to feed and offer substantial gifts to all those in attendance, so organizing a feast of this scale would usually be done with at least a year’s lead time. It is a statement to the sense of unity and purpose for the clan that they were able to pull the feast off so well with such short notice. It is also a testament to how important this is to the people up and down the coast that so many were willing to travel to remote Haida Gwaii to bear witness to the business of the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas.

About 20 meetings were held by the clan once the NEB letter came to light. As multiple members of the clan said, everyone was invited to come and have their say and people worked to make sure of that, reaching out to the clan to make sure that everyone knew about the meetings and the proceedings. While discussions were often difficult, being about and amongst family members, the meetings were well attended and the decision to disrobe the two men was well supported.

With the backing of Enbridge and high priced lawyers, Goertzen and Ingram have threatened a libel lawsuit against litl’xaaydaGa Ginawaan (Darin Swanson) if the feast was held. Despite the threat of lawsuit, the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas went ahead with the feast. This feast was Haida business, not Canadian, and so Haida law stands first. (The men who signed the LLP NEB letter have not made themselves available to media for official comment).

What is a potlach

For First Nations of the region, a feast or potlach is a place of ceremony, a place of ‘doing business’. Based around the gifting of food by the hosts, it is far more than simply an apolitical cultural practice. It is a place where meaningful political actions of the community are conducted, where community roles (as signified by ‘names’) are assigned and where this business is witnessed. It is the center of the traditional legal system, based on oral tradition. The assembled guests act as witness and through their participation, they affirm the business being conducted at the feast and carry the stories to their communities. Clan meetings leading up to a potlach set the ground, making sure that all is in order and that there is consensus on the rightfulness of all business to be conducted. A well-attended potlach, witnessed and affirmed by members of the house, clan, nation, and visiting nations, attests to the legitimacy of the business. Challenges to the business being conducted would come through organization of a sizeable contingent of opposition at a feast or in organizing a counter-feast of a larger scale, with more in attendance. A clan would ideally only hold a feast if they knew that such a challenge would be insufficient to block the feast. An individual or small group cannot through accusation alone challenge the legitimacy of feast business, but would have to materially demonstrate such through their own physical mobilization of clan or nation members. This is the power of the feast; how physical participation makes it so obvious whether there is or is not support in the community for the business attended to.

For many decades such feasts were illegal and suppressed violently by the Canadian government. Simultaneously, the Canadian government imposed the Indian Act Band Council system of governance to undermine traditional law and facilitate assimilation and cultural genocide. As the band council system came to dominate and traditional governance was disempowered by the Canadian military, this often meant that potlaches, held in secret, became relegated to ceremonial roles that have less political or economic impact. Still continuity has been maintained, as potlaches continued in secret. As the nations are growing stronger, more able to resist the colonial government, and as they are receiving acknowledgement and support from the Canadian Supreme Court, they are reasserting the political meaning of the feast and traditional law, which was never forgotten.

By bearing witness at a feast, one commits oneself to the truth of what one witnesses. As one participates physically in the songs and dances of the feast, one affirms with one’s body one’s commitment to the social order established through the feast, an order that centrally is about respecting the land and community and is about reciprocity and giving.

In the context of historical colonial suppression, there is also necessarily a movement to repair the system from the damage done, to learn how to protect the system from damage from new colonial strategies. This feast is part of that movement. In interview with Eugene Kung, Christine Martin spoke of how the nonnies had said that this had not happened in their days because men were taught from a very early age what their responsibilities were, how they were expected to listen to their clan and matriarchs. This kind of lack of upholding of chiefly responsibilities would have been less likely in a time when traditional practices were not so consistently suppressed. “Colonization has had an impact. A lot of our teachings have been lost. The role of the chief needs to be taught. We walked away with a better understanding of that.”

The feast: Raven Always Sets Things Right

The feast, attended by over 600 hundred[4], was hosted by litl’xaaydaGa Ginaawaan (Darin Swanson) and the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas clan. While many within the clan do feel that Ingram and Goertzen brought shame upon themselves, it was articulated multiple times during the feast that it was not a ‘shaming feast’, but was strictly carrying out the business of making sure that those in the role of litl’xaaydaGa were willing to carry out the responsibilities of litl’xaaydaGa. It was emphasized that both Goertzen and Ingram are invited in their own time to go through the process of reconciliation with the clan and hold their own feasts to reestablish themselves honorably in relationship to the clan. It was a powerful ceremony attended and witnessed by chiefs from communities throughout BC also threatened by proposed oil and gas projects. Haida and visiting chiefs spoke to standing firm together against these projects, giving moving and powerful speeches that brought tears to the eyes of many who bore witness.

Many in the clan expressed how there was a lot of apprehension and tension going into the feast. This had not been done before in living memory and involved a radical and strong stance against the actions taken by some in the clan. The divide and conquer issues being confronted by the community were long standing problems, so mixed with the feeling of rightfulness in challenging it was the fear of what might happen. For me as a guest, however tensions were not apparent as Crystal Robinson made the rounds shaking hands with and welcoming every one of the 600 + guests in attendance. As guests flooded in, there was a sense of togetherness and shared purpose that was palpable and exciting. This sense of togetherness built rapidly as everyone arrived and saw how well the feast had been prepared.

After a formal entering procession with local and visiting chiefs and the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas, the event opened with a song and grounding by community leader, Vern Williams, and with the spreading of eagle down by masked dancers of raven and eagle, as well as dances of frog, wolf, sun, hummingbird, and others. One particularly poignant traditional dance that set the tone for the evening was performed by local carver, Reggie Davidson, “Taking off the Mask”. With traditional rattler viscerally focusing attention and guiding Davidson, the revealing and removal of the carved mask symbolized and embodied removing pretense and secrecy and establishing honesty in relationships, a comment on the need for transparency, the stopping of secret dealings with destructive industries behind false social masks.

After the initial offerings of songs and dance, Ginaawaan clearly laid out the business of the clan, read the letter sent by Ingram and Goertzen and named clearly the justification and decision of the clan to no longer recognize the two as litl’xaaydaGa and to no longer recognize their names as chiefly names. He then explained the copper that was created for the feast, to mark this feast as an historic event.

A ‘copper’ is a shield, made out of copper. Coppers are considered amongst the most important and heavily ‘weighted’ objects held by a clan, symbol of wealth, history, and honor in living life in a good way according to Haida beliefs. In 2014, Haida broke a copper in Victoria and again in Ottawa as a ritual challenge to the province and federal government to act respectfully toward First Nations peoples and in a good way toward the environment and future generations, particularly around dealings with oil and gas.

For this feast, a copper was created that had engraved on it the expectations of someone who takes on the role of litl’xaaydaGa. These duties include transparency in all dealings, taking direction from the clan and matriarchs, and protection of the land and seas for future generations[5]. Those in attendance frequently interrupted Ginaawaan with cheers of approval as he announced the business of the clan in disrobing these men and again as he read out the expectations of litl’xaaydaGa. The copper was then danced through the hall by Ginaawaan, joined by the women of the clan. Quoting Darin Swanson from the feast, “This is dirty oil infiltrating our community and picking us off one by one. This is a modern day smallpox epidemic. There is an infected blanket in our community and it is time to burn that blanket.“[6]

Though the event started for some with apprehension, tensions in the room dissolved as those assembled felt the sense of unity and the sense of rightfulness and respect in the carrying out of the clan business. A plentiful meal featuring salmon and halibut was served by the clan, and light and happy spirit filled the hall, recognizing this feast for the groundbreaking feast that it was, not just for the Haida, but for First Nations throughout BC.

Peter Lantin, president of the Council of the Haida Nation, speaking of the necessity to strengthen traditional non-colonial governance

After the meal, Chiefs from other Haida clans spoke to how well the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas conducted their business, finding inspiration in how they set things right. Renowned Haida carver, Iidansuu (Jim Hart) talked of looking forward to fighting together in defense of the lands, seas, and little ones. Wigaanad (Sid Crosby) spoke of how heartbreaking and sad it is that this needed to be done, but that it showed the strength of the Haida Nation, that what the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas did would be remembered forever. Skil Hiilans (Alan Davidson) talked about how these divide and conquer tactics and the paying off of chiefs is nothing new, that he was proud to be called a trouble maker for standing up against it. Taaw.ga Halaa’ Leeyga (May Russ) echoed sentiments of sorrow at the circumstances and that it was time to heal. Her fiery call for standing firm together with other First Nations in the face of threats from oil and LNG was met with resounding cheers in the hall. Gya awhlans (Roy Collison) echoed all in the necessity of everyone, especially chiefs, to follow their matriarchs. After naming the line of women whom he comes from and from whom he gets his clan identity, he spoke with a voice almost as loud as the assembled cheers of the crowd about how the Haida owe respect, owe their existence to their nonnies (aunties and matriarchs). Peter Lantin, president of the Council of the Haida Nation who spoke about the awkward position of being a representative for the colonial government, thanked the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas for acting as a role model in setting things right and spoke of how the other clans were watching, spoke clearly to the necessity for clans to exercise their traditional (non-colonial) governance.

Chiefs from around the province applauded the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas as well for how how they set things right and set their course in a good way. Simoyget Algumhkaa, (Murray Smith), visiting from Lax Kw’alaams, talked about how moving it was and how inspiring it was to the people of Lax Kw’alaams fighting against LNG on Lelu Island (Lax U’u’lu). Chief Namoks (John Risdale), visiting Wet’suet’en chief of the Tsayu clan, thanked the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas for allowing him to witness what he saw as an act of respect… respect for self, for clan, for each other, protecting the land, freedom, and culture for the little ones there to witness. Chief Nekt (George Muldoe), visiting from the Gitksan and named plaintiff in the Delgamukw Supreme Court case, talked about how in his own community, chiefs were being clandestinely paid off in back rooms with $100k signoffs and that he was happy to see what he saw at the feast and that the smoothness of the ceremony spoke to the unity of the clan. Skil Luce (Reuben George), Sundance Chief from the Tsleil waututh, particularly moved the assembly as he talked about his travels to other countries meeting with other indigenous people involved in the same struggles against abusive resource extraction industries and corrupt colonial governments. Many eyes teared up as he spoke of the violence and murder that indigenous people he met were facing, the cancers spread in the name of tar sands oil expansion, the way that colonial governments have worked so consistently to sever people’s connections to the land and waters. The walls of the hall vibrated with cheers as he put words to the shared sentiment that we cannot be the generation that stops fighting for the land, our peoples, our children and that even if we lost in the courts, that we would do whatever is necessary to stop these companies and govern these lands ‘as we see fit’. These fights connect across the country to fights against the Kinder Morgan pipeline expansion and Woodfibre LNG facility in the south of the province, fights against fracking in Micmac territory and across the continent to fights against oil pipelines currently gathering thousands in the Dakotas.

At the end of the feast, the women and then the men came together to dance their affirmation of the rightfulness of the actions of the feast. This integration of the body into politics is striking as an outsider. As Ginaawaan describes it, “The singing and dancing is celebrating, it’s kind of an agreement. We are singing and dancing together, dancing our agreement.” I felt myself how the active involvement of the body in the expression of politics, absent from mainstream conceptions of political process, created a unique and strongly felt sense of commitment to the unified position of the clan and those assembled.

Also, for me as a witness from outside the community, I was struck and inspired by the emphasis on women’s roles. One of the regular refrains of the feast was reference to taking direction from the matriarchs, of men being pushed into doing the right thing by the ‘bossy Haida women’ (met with knowing laughs from the room). Men at the feast and in interviews talked reverently about listening to and learning from their nonnies (grandmothers and elder women relatives). As Lisa White explains, “The backbone of the nation is built by women. Traditionally our Haida women are really strong, business minded and industrious. Traditionally they would be involved in trading and the business end of things, making sure that things are done right. We learn from our aunties and our nonnies, learning how to behave. They are very important people in the community. A lot of our aunties lived through changing times, but they had older ways taught to them … If you have families with lots of women, you are rich. If you have lots of daughters, you are wealthy.” Christine Martin, in an interview with Eugene Kung, named it as a sign of the legitimacy of the feast, recognized with relief by all in attendance, the gestures of approval given by the matriarchs. It is a burden that the (mostly male) chiefs take on to do the politicking. They take their direction from the matriarchs and it is the fire of the matriarchs that inspires the community[7].

litl’xaaydaGa Allan Davidson… proud to be a trouble maker for standing up against divide and conquer politics

As declared at the feast under the approving eyes of matriarchs and assembled witnesses, Francis Ingram and Carmen Goertzen no longer hold names as litl’xaaydaGa, no longer represent their clan. The names they held are considered tarnished and no longer chiefly names. The clan is united against tankers moving through or near its waters, united against the dangers of oil and gas development in the region[8].

Immediate reactions and movement in community

Enbridge’s permit was revoked by the courts, subsequent to the letter these men wrote to the NEB. This feast was, then, less about the immediate threat of Enbridge, more about establishing better leadership as they move forward on other fights, including those against LNG and against the logging that is still ravaging Haida Gwaii. Despite previous victories against wildly destructive logging, helping establish some protected areas on Haida Gwaii (most notably Gwaii Haanas), less devastating logging practices, and limited Haida influence over logging, there is almost uniform dissatisfaction with current logging practices. As the old growth forest areas surrounding the traditional village sites of the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas clan are currently under immanent threat of logging, many talk about it being time to assert their rights with a new wave of blockades against illegal and destructive logging on their territories. The ongoing forest and salmon habitat destruction makes many Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas wonder why anyone other than the clan itself should have any say over logging on traditional clan territory[9].

Another thing that should also be understood by outsiders is how family is more important, even central, in many First Nations communities than it is for many of us raised more centrally in a colonial state. As such, there is a strong sense of family connection, even in these moments of conflict. Where we might jump to ‘otherizing’ and isolation, there is a sense that despite the wrongs done, these men are still family. Many in the community were in fact hesitant to talk to me in any official way because they did not want to make the fissures between these men and the community worse. Even some of those who held the most critical positions on the actions of Ingram and Goertzen expressed a desire for reconciliation and coming back together as family, as clan. As Crystal Robinson of Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas said, this is part of what made the work of holding this feast such difficult emotional work, juggling the desire to not alienate members of the clan with the clear responsibility to uphold Haida law responsibly, to maintain relationship to the earth in a good way. The feast was held respectfully, focusing positively on the unity of the community and movement forward, rather than dwelling on the missteps of the ex-chiefs. The respectfulness of the event was witnessed and affirmed by the Haida and visiting chiefs as well as all in attendance.

While the clan wanted to hold Goertzen and Ingram accountable, there was never a sense of ‘kicking them out of the community’. As Darin Swanson said, there was consistently a desire to ‘hold them up’ – to support them in doing the right thing. Everyone makes mistakes, and they were invited to publicly rescind the letter to the NEB. Even as they refused these opportunities and had their chiefly names taken from them, May Russ made clear at the feast that they were invited in their own time to do the right thing, make amends with the community and hold feasts to restore themselves in good standing with the community. This dividing of families is felt by many to be one of the more painful consequences of the divide and conquer tactics of industry.

During my time on Haida Gwaii, I talked to many clan members who filled me in on back details and shared concerns about mending hurt feelings in the family. There was a great relief and satisfaction in how well the event went off with such minimal resistance[10].

While a very small minority of the community more connected to Enbridge money has made some complaints about the feast and the process, claiming the feast is not legitimate, the sense of enthusiastic unity at the feast was strong and palpable, with frequent roaring cheers reverberating around the hall as the people gathered affirmed the righteousness of the business done at the feast. The matriarchs of the clan standing in support made this clear, and when I showed video footage of the feast to those who were unable to attend, they were impressed. It was clear to them that all was done correctly, powerfully, traditionally. This unity was likewise reflected in my own conversations around Massett and Old Massett in the weeks following the feast, where I found it hard to find any who did not support removing these two from their positions of leadership.

Representations in media: Divisions?

The event was quickly reported by regional media. This is reflective of how important and provocative this event was seen to be, as such a landmark action. However, many of the articles portrayed the event as a sign of deep division in the community. This was not my experience in the weeks I spent on Haida Gwaii after the feast. The actions of Goertzen, Ingram, and the 6 other Haida who signed the letter in support of Enbridge were seen by everyone I talked with as inappropriate and a betrayal of the Haida values and position.

Haida carver, Gwaii: “They [media] got it wrong to describe it as a sign of division. The results of the feast are a sign of unity. This is a small number of people after Enbridge has been making all kinds of promises, coming up here with bucket-loads of money trying to get any kind of sign [of agreement with their proposed pipeline] …”

There is a habit in media to try to give multiple sides to a story. The problem with this is the portrayal of ‘false balance’. If media gives equal time and space to two positions, it gives the impression that the two positions are equally valid or that there is equal support for the two positions. This was famously lambasted by John Oliver around climate change, where 97/100 climate scientists found that the evidence for human caused climate change is irrefutable[11] and yet media kept giving equal time to both climate scientists and climate change deniers (usually funded directly by fossil fuel companies). Fossil fuel companies recognized this and so invested in keeping their own scientists to fuel this false impression of conflict within the climate science community, strategically fostering confusion on the issues to their benefit. This finally lead to media outfits, such as BBC, declaring an end to such ‘false balance’ reporting with regards to climate change. The reporting on First Nations politics in general and the feast in particular has followed a similar dynamic, with the Vancouver Sun reporting on this feast as a sign of deep division in the community. Media sells better when it reports on conflict and problems rather than solutions, so the pressure to steer an article in this direction is understandable. Even Discourse Media, mostly doing an excellent, well researched and responsible job of reporting on the feast (as well as on First Nations politics in general, which is much needed), uncritically repeated the claims of one of the chiefs that this is a sign of a ‘war within the community’. The war in this case is not between halves of the community but between the community and a very few being bought off or coopted by industry in order to fuel these stories of false balance. This is ‘divide and conquer’ tactics in action.

Namoks, visiting Wet’suet’en chief of the Tsuya clan: honored to be invited to witness this act of respect for self, clan, the environment, tradition.

The feast hall was packed. This is the strength of the feast system; if community members do not support the positions and assertions of those holding the feast, then they do not show up and it is reflected in poor attendance. The clan demonstrated itself as united against Enbridge. Ingram and Goertzen showed that they lack community support, being unable to defend their own actions in clan meetings and unable to rally more than one or two percent of the community to support their stance. There is no support that I was able to see for the view that the community is deeply divided, but instead saw that there is a small contingent of the community supported by Enbridge money who have worked to portray false divisions.

While these few still try to claim that the feast was not legitimate, the clan is moving on with potlaches being scheduled for the next year to bring in the new house chiefs. If the objectors want to press their claims, the onus would be on them by Haida law to hold their own potlaches. Given the paucity of protest at the feast and the lack of support I observed in the community, this seems quite implausible. Again, this is the strength of the potlach system, the visible, transparent, embodied demonstration of support, now easily documented through film and video.

Taking this further, one thing that several people were quick to point out is that the positions of these men should not be seen as ‘enthusiasm for Enbridge’. Where there has been debate in the community, it has not been about whether to enthusiastically embrace the pipeline project and subsequent tankers as a boon or not. It has been more about whether it can be resisted or not. This must be understood in the context of the disenfranchisement of First Nations peoples, the theft of their resource bases, and the centuries of full assault on their cultures and social capital. For the Haida in particular, no one views this as ‘good for the Haida’. Some are tempted from a place of disenfranchisement to get what they can out of a system that appears out of their control. There is within the mix of voices in the community (as well as other First Nations communities) this defeatist voice which is overwhelmed by how severely oppressed First Nations people have consistently been in North American. From this perspective, there is a desire to give in and get whatever can be gotten to avoid being even more severely hurt. Gwaii: “Right from the start Haida Gwaii has been united and pretty much unanimous. There has not been any wavering on the front of how we as a community felt about having pipelines come to the coast and particularly tankers coming by our islands. They [Enbridge] needed to show some crack in this united front that is Haida Gwaii. I know all those guys that signed that letter. They are not evil or anything like that. Maybe greedy… they signed that letter by rationalizing to themselves that they could do that. I’m pretty sure they do not want oil tankers going by their coast. They wanted a piece of the pie or maybe they, believing in the inevitability, figured they might as well benefit … but it is not inevitable.”

This is not the dominant voice of the community, but it is understandable. These men, while perhaps greedy in the moment, were not necessarily embracing oil tankers on the coast from a position of power, but are better seen as trying to get what they can out of a bad situation, where their community has had much of its resources and wealth stripped from them. Of course, the oil and gas companies play into this insecurity and exaggerate it by attempting to coopt and buy off these members of the community. Through short-term financial support oil and gas companies seek to inflate these coopted individuals’ status within the community. It is understandable how out of desperation for their communities mixed with the enticements of quick money, there are usually a few who give in to these ‘divide and conquer’ tactics.

Repercussions and reflections: What this means for Haida and other communities

I stayed in Haida Gwaii for a week and a half after the feast, to explore the island and community, to interview those involved with the feast and to talk with people in the community about the feast. The quickly posted photo series and statement about the feast I put on Facebook were reshared widely, and gathered responses of support and inspiration from around the region.

In the Haida community, there is movement in other clans to ‘clean house’ within their hereditary leadership, with the other two hereditary chiefs who signed the NEB letter likely targets. Roy Jones Jr., who was a Haida chief from another clan who signed the letter, has been put on notice by his clan matriarchs that he no longer represents the clan. This is not just about the hereditary system, however, as there is also a movement afoot in the town of Old Masset to hold community votes to change the Indian Act band council government[12]. Many are also dissatisfied with directions that the band council has gone and want it to reflect better the will of the community.

The issues faced by the Haida in trying to live their responsibilities to protect the land and sea in the face of divide and conquer strategies of industry are not at all unique but are faced by First Nations throughout Canada and by indigenous people all over the world. This feast follows recent elections in the Wet’suet’en community of Moricetown, where grassroots land defenders organized to elect people, including Unist’ot’en leader Freda Huson, who more clearly act on traditional values and the will of the community in fighting the expansion of fracked gas and who do not engage in the kind of legal overreach that is encouraged by oil and gas industries desperate for the image of having gotten First Nations buy-in. I heard from members of Tsimshian, Gitksan, and Wet’suet’en communities about similar processes either being organized or contemplated in their communities. This feast is likely to be one of many as Nations clean house within their leadership, both hereditary and colonial band council, bringing clan representation more in line with traditional values and law. Traditional governance is being reinvigorated. Other communities are likewise engaging in clarification of roles of spokesmen/chiefs and in some cases reassessing whether current name-holders are fulfilling their obligations.

Speaking as an outsider, this is something we all need to pay attention. Systems in which we are all complicit are directed by forces that are willing to destroy communities and our shared environmental base for their own short term profits. The governance issues of First Nations communities are something that affects us all. It is also something that we all influence as we are complicit with or resist these attempts to undermine and misrepresent First Nations law.

Of course, industry is not taking this lightly. The libel lawsuit funded by Enbridge against both Darin Swanson and Peter Lantin is a looming threat. The fight over representation and misrepresentation of First Nations is incredibly convoluted. Even though the lawsuit is likely to be found to have no merit, it is just one more strategy of industrial actors to weaken and drain opposition, an attempt to make others afraid to follow suit. From what I have heard, it is mostly just pissing the Haida off and motivating them further. The feast hall reverberated with cheers as Darin Swanson spoke there of how Canadian law has no place in First Nations governance, of how “Haida law doesn’t need lawyers, Haida law is the voice of the people!”

There are more oil companies than just Enbridge that the Haida face, more fossil fuel issues than oil, and more industrial environmental threats than just fossil fuels. Speaking about the current outrage amongst the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas about the clear cutting that continues on the island, Lisa White said, “I would like to see these islands go back to the way Haida utilized these forests. Clear cut logging should be outlawed. We all feel strongly that it has to stop. Any opposition to that is very minor… We are going to have to make a stand here very soon … We want to keep our fish and tree populations healthy.”

Engraved on the copper created for the feast, “Raven Always Sets Things Right”

litl’xaaydaGa “The Chief”

In taking the name to which they are entrusted as chief of the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas, our chief must strive to excel in moral and ethical standards.

As litl’xaaydaGa I must not be offensive to others. I must not bring undue attention unto my name, nor put myself above another. As litl’xaaydaGa, I take this position for the love of my people and will nourish and protect our Clan, always guided by the principle of Yahgudaang. I will take direction from our Clan. I will represent the Clan in social, ceremonial and political business of the Haida Nation. I will seek and learn, share and protect the necessary knowledge to ensure that our traditions are upheld. As litl’xaaydaGa, I will maintain harmony within the Clan, and peace and unity within the Haida Nation. When necessity demands, I will take a position of strength if my Clan directs me. As litl’xaaydaGa, I WILL HOLD FOREMOST THE WELLBEING OF HAIDA GWAII, ITS AIR, LAND, WATERS, AND CREATURES FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS.

While Gwaii talked of how the Lyle Island protests and subsequent blockades have brought much positive change, the Haida are not all the way there yet. The Haida have in some form taken over much of the logging on the island, improved how it is done and reduced its rate, but it is still industrial logging that, as a carver, hurts his soul. In discussing the many resource economy issues the Haida currently face, local carver Gwaii described how “At one point this island supported 40,000 people and it did that for millennia. Now it’s being asked to do that for the world… [wood, fish, clams] it’s all getting shipped out. We need to be careful of this bottomless hole of a mouth out there of the rest of the world trying to be fed… [these tankers are] forever dribbling their detritus into out waters. That’s already a problem… a spill will happen. If we accept these tankers, we are accepting a big spill. We are under no obligation to satisfy the appetite of the world for grinding the rest of their resources into dust.”

As Eugene Kung writes, “The Haida [through this feast] were able to use their own laws and procedures to undermine the tactic that industries and governments have used forever: dividing and conquering communities by cherry-picking individuals to try and give the illusion of support and consent.” A big ‘Hawa’a’[13] to the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas clan for the political work you have done in setting things right and for taking the very emotionally difficult steps to act in a good way[14]! This event stands as an inspiration to other communities facing similar issues in their own communities, confronting the ‘divide and conquer’ strategies of these greedy companies.

For other references

For alternative write-ups on the feast, see Eugene Kung’s blog article from West Coast Environmental Law as well as Trevor Jang’s articles for Discourse Media on the feast and the background issues.

For a photo and video-still series from the feast, here’s my facething album.

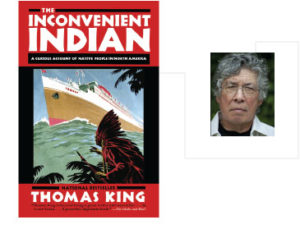

I also can’t recommend enough Thomas King’s book, “The Inconvenient Indian” for a whirlwind primer on the barbarity of US and Canadian colonialism and genocidal actions and intentions against the first peoples of the Americas.

—

[1] The Supreme Court has been consistently opposed by federal and provincial executive authorities who continue to try to undermine First Nations governance.

[2] This request was in the end rejected by the Canadian courts, and Enbridge’s permit was revoked in June 2016 by the courts because of lack of real consultations with First Nations.

[3] This ceremony had not been carried out in living memory, though similar changes in leadership (if more violent) based on misconduct were part of oral histories of the Haida. A similar ceremony is documented by Franz Boas (Tsimshian Mythologies, 1916) amongst the Tsimshian, where a feast was organized to strip the chief name from someone who was found to not be holding it legitimately, and more recently such name stripping feasts have been reported amongst the Gitksan, though not yet over resource control issues.

[4] This estimate of attendance is based on video footage I took from the event at the peak of the feast. This is likely an underestimate of overall attendance, given how there were many who arrived late and many who could not stay for the whole event.

[5] Engraved on the copper created for the feast, “Raven Always Sets Things Right”

litl’xaaydaGa “The Chief”

In taking the name to which they are entrusted as chief of the Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas, our chief must strive to excel in moral and ethical standards.

As litl’xaaydaGa I must not be offensive to others. I must not bring undue attention unto my name, nor put myself above another. As litl’xaaydaGa, I take this position for the love of my people and will nourish and protect our Clan, always guided by the principle of Yahgudaang. I will take direction from our Clan. I will represent the Clan in social, ceremonial and political business of the Haida Nation. I will seek and learn, share and protect the necessary knowledge to ensure that our traditions are upheld. As litl’xaaydaGa, I will maintain harmony within the Clan, and peace and unity within the Haida Nation. When necessity demands, I will take a position of strength if my Clan directs me. As litl’xaaydaGa, I WILL HOLD FOREMOST THE WELLBEING OF HAIDA GWAII, ITS AIR, LAND, WATERS, AND CREATURES FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS.

[6] For those not familiar with the history of colonization, the last reference is to the recent historical use by English traders of blankets infected with smallpox as malicious ‘gifts’ to First Nations to murder them through what we would now call biological warfare in order to seize their lands and resources. The history of western capitalist abuse of First Nations communities runs long and deep, something that many in the dominant culture fail to entirely appreciate, except as superficial historical footnotes. For the Haida, this wound runs particularly deep as over the 1800s, 90% of the Haida populations was wiped out through successive waves of disease

[7] While the underlying traditional respect for and power of women is similar amongst the nations of the region, specific traditions vary. Christie Brown (currently occupying Lelu Island as part of Gitwilgyoots territory defense against LNG) told me as I was heading to Haida Gwaii a tradition of some of the Tsimshian which captures this role for women. While the men would usually have the chief role and do the political work, it is supposed to follow the will of the matriarch. Symbolizing this, the chief would not put on his own robe or take it off at ceremonies, but would have this done for him by the women of the clan. This action represents how the authority the chief carries into ceremony is not his, but is loaned to him by the women, and that it can always be taken back.

[8] The Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas, the largest of the Haida clans, is united against all fossil fuel expansion in the region, whether it be bitumen or fracked gas (LNG). The Haida, as all communities in the region (First Nations and not), are united against the movement of tar sands oil to the coast. The furor that arose over the issues of tar sands oil acted as a smoke screen however under the cover of which LNG (liquefied natural gas) was able to gain some acceptance and limited approvals. Resistance to LNG has been rising in the last years, with several adamant occupations arising to prevent the building of pipelines and export facilities. These include the Unist’ot’en and Luutkudziiwus (Madii Lii) camps obstructing pipelines and the Lelu Island occupation of Gitwilgyoots blocking the building of an LNG facility in essential salmon habitat of the Skeena. On the one hand people recognize the pollution and social destruction coming from fracking itself and the ensuing effects on climate change (worse than coal), but there is also the recognition that the building of any such pipeline would facilitate the fracking and pollution of the Skeena watershed itself (the third largest salmon run in the world) and would inevitably mean the movement of tar sands oil to the coast through these same pipelines within a decade. The Yahgulaanaas/Jaanas clan, as many others, stands united against both oil and gas.

[9] Canadian Supreme Court cases (Delgamukw (1997) and Tsil’qot’in (2014)) have supported this view, ruling that it is the traditional hereditary governance structure which has control over the land and that all activity on the land needs to get their prior informed consent before proceeding. This makes the logging in their territory illegal, but getting law enforced often only happens through show of force in First Nations communities.

[10] There were 4 people in total who showed up to the event and silently expressed objection to the proceedings. The contingent of objectors was actually so minimal that it had to be pointed out to me where they were in the video documentation I made of the event, lost as they were in the overwhelming sea of support for the clan shown by the enthusiastic hundreds in attendance. If they are actually representative of larger numbers who decided not to attend, this was not at all clear from my two weeks of hanging out and talking to people randomly on the streets of Massett and Old Massett. By Haida law, it would be up to them to demonstrate their support through a counter feast, but that seems extremely unlikely, to put it mildly.

[11] The numbers now are actually more like 99.5/100 climate scientists affirming human caused climate change.

[12] This is the same Old Masset band council chief who was involved in the scientifically laughable and politically questionable iron-oxide ocean dumping carbon offset scheme back in 2011.

[13] ‘Thank you’ in the Haida language

[14] A big thanks also to Crystal Robinson for helping me make more connections, offering me a place to shower, and for the awesome elk stew and other meals, to Patrika McEvoy for helping me make connections here (and for providing all the salmon we ate at the feast (wow!), to Goldie Swanson for quickly giving me the OK to film with 1 minute of explanation, to Christie Brown for encouraging me to come and for currently holding down the occupation at Lelu Island, and a big thanks to all the inspirational Haida I met and talked with while there!